LIFE IN HAPPY VALLEY

FARMLAND TO FACTORIES

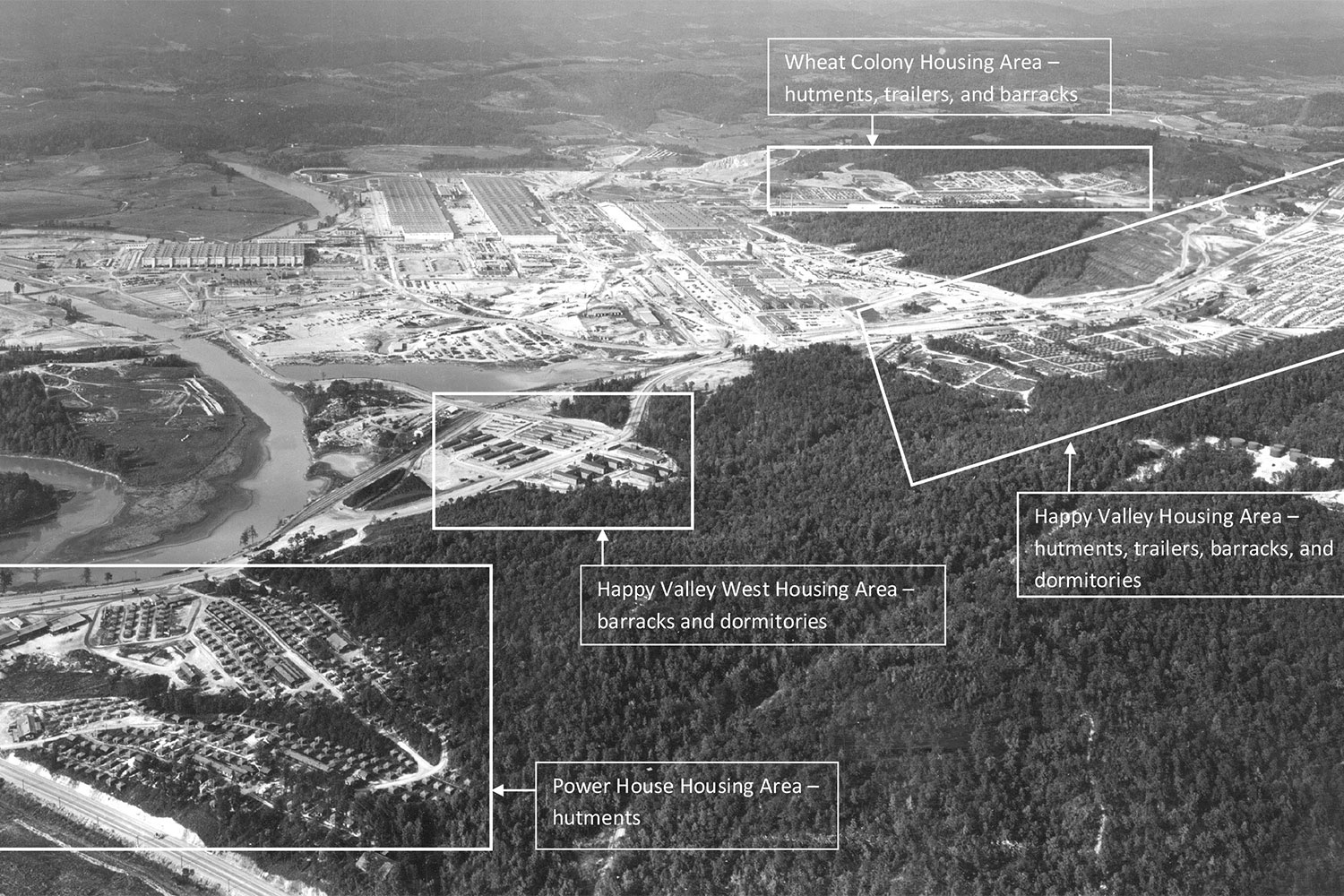

Secret cities emerged overnight to support weapons production. At the western most boundary of the military's new reservation in East Tennessee, the war effort engulfed the tiny Wheat Community (population 1,000), replacing farmhouses and fruit trees with massive concrete and steel structures that would produce the world's first enriched uranium. The boomtown that materialized from the sleepy pastureland became known as Happy Valley. Only steps away, a second community emerged; Happy Valley's smaller "neighbor to the East" would be called Wheat Colony.

WHEAT

Originally known as Bald Hill, the community was renamed Wheat in 1881 when the post office was established by Henry Franklin Wheat. Community residents shopped or mailed their letters at the McKinney General Store, filled their gas tanks at the Watson Service Station, and likely attended services at one of three churches - George Jones Baptist, Crawford Cumberland Presbyterian, or Methodist. Students in grades 1 through 12 attended the Wheat School. The Masonic Lodge was a "Moon Lodge," meeting on or near the full moon each month. Peach orchards blanketed the countryside; in 1935, Highland Orchard, Wheat's second largest orchard, shipped 20,000 bushels.

Learn More

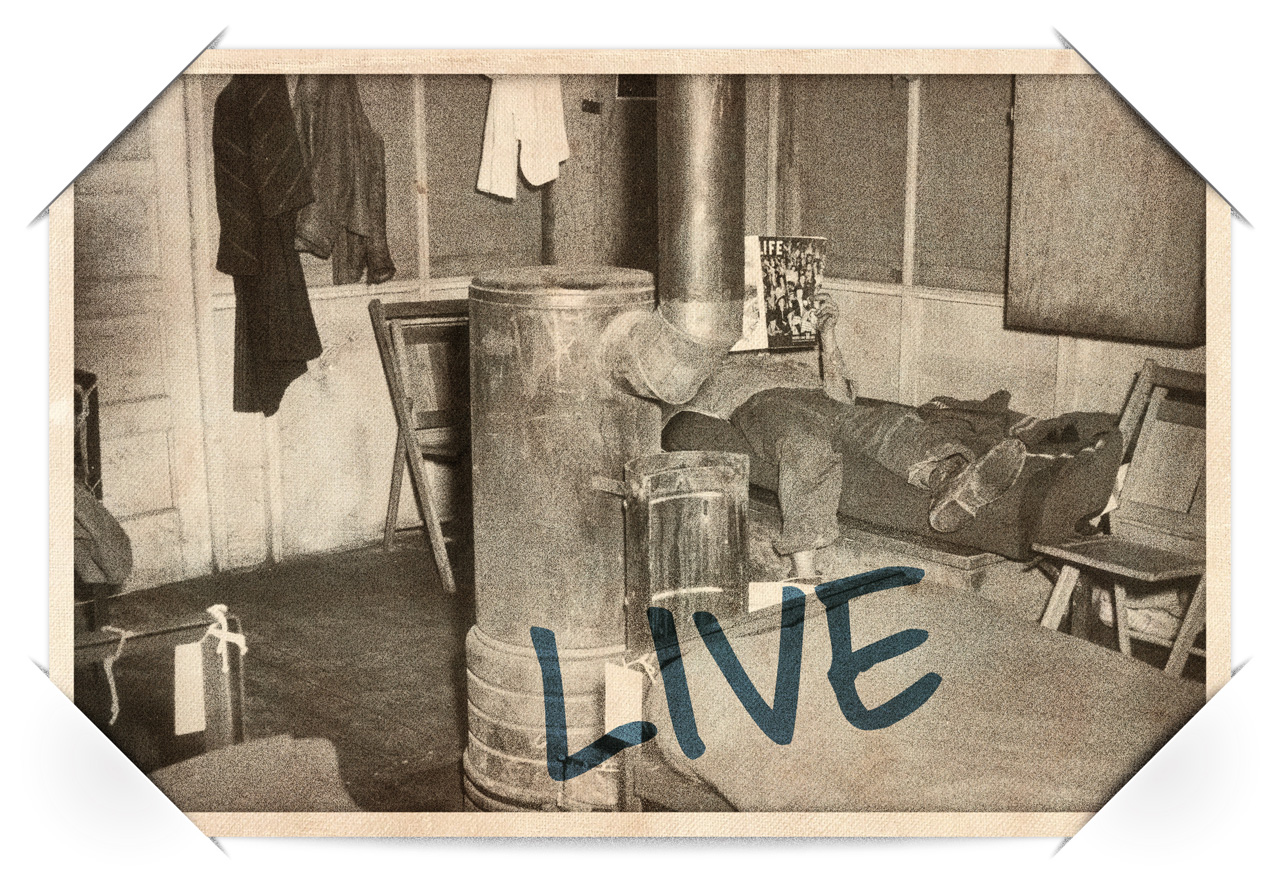

LIVE

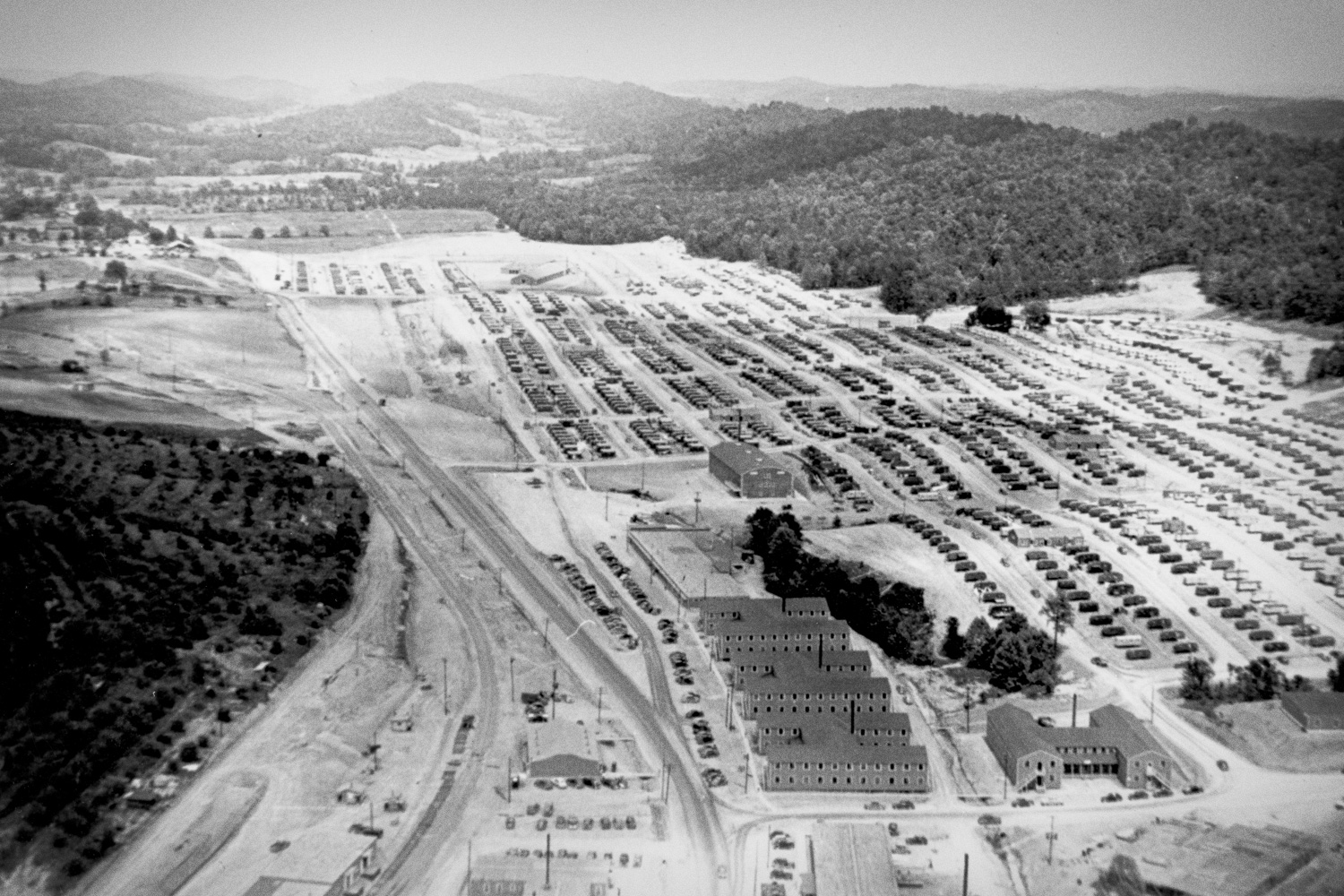

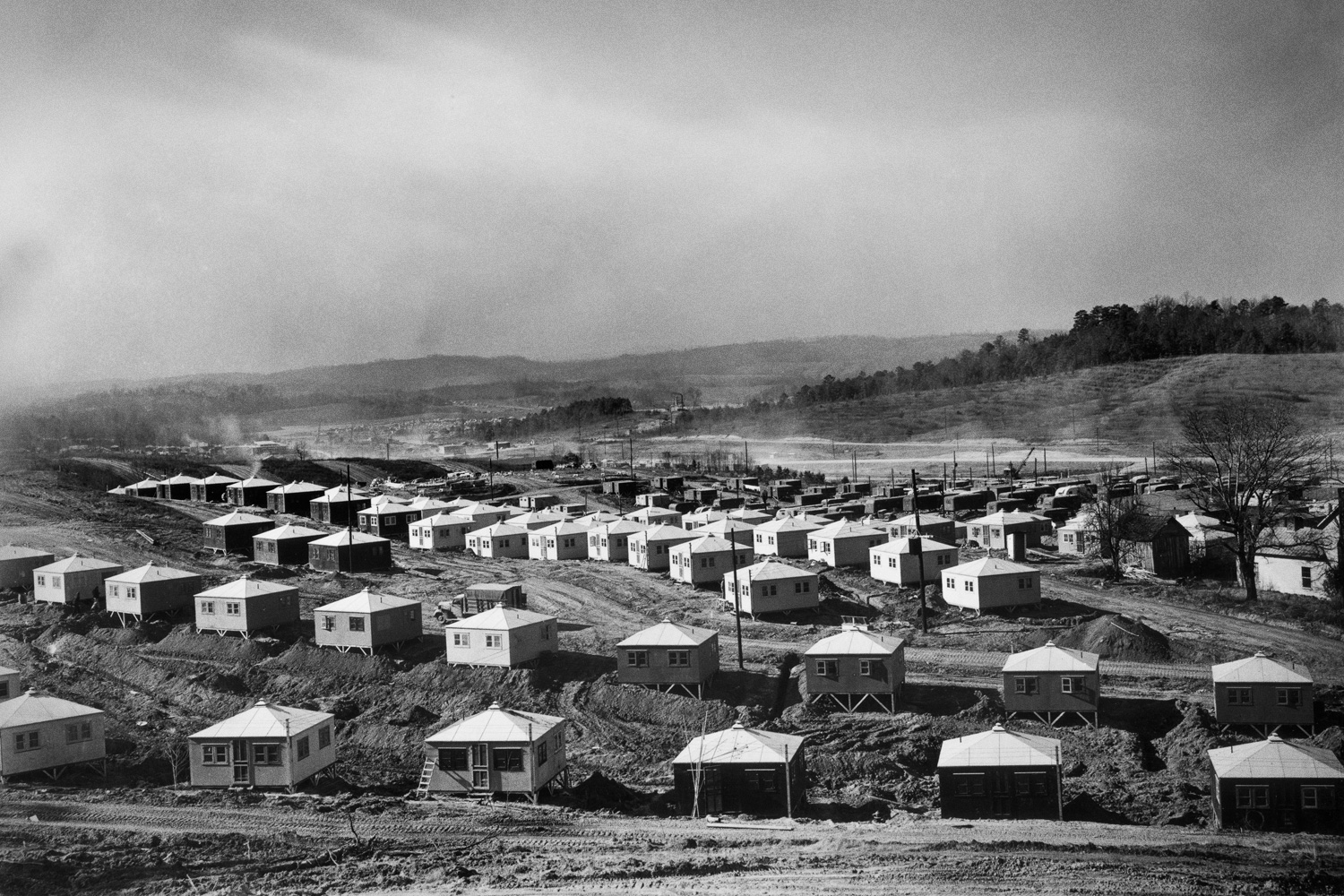

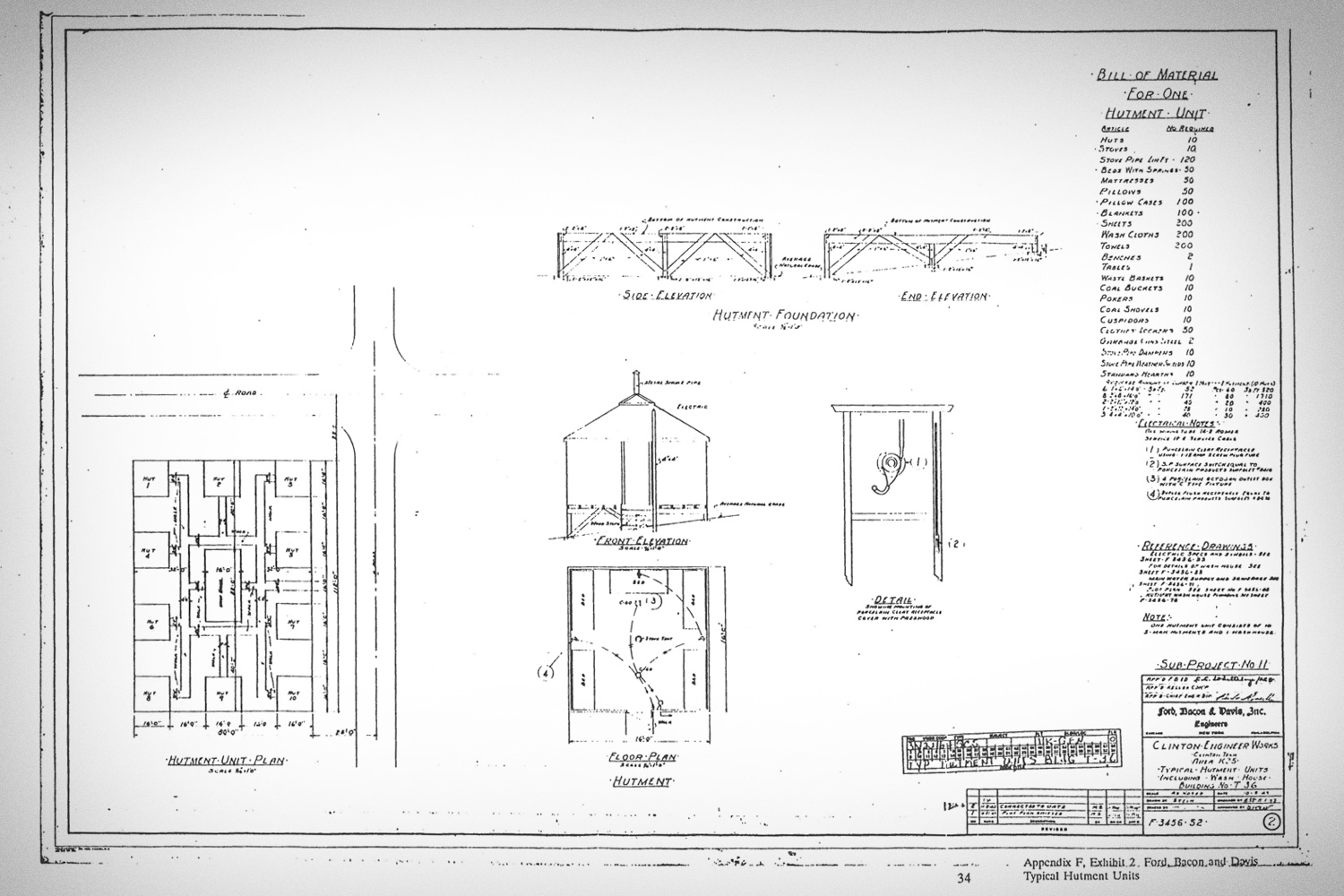

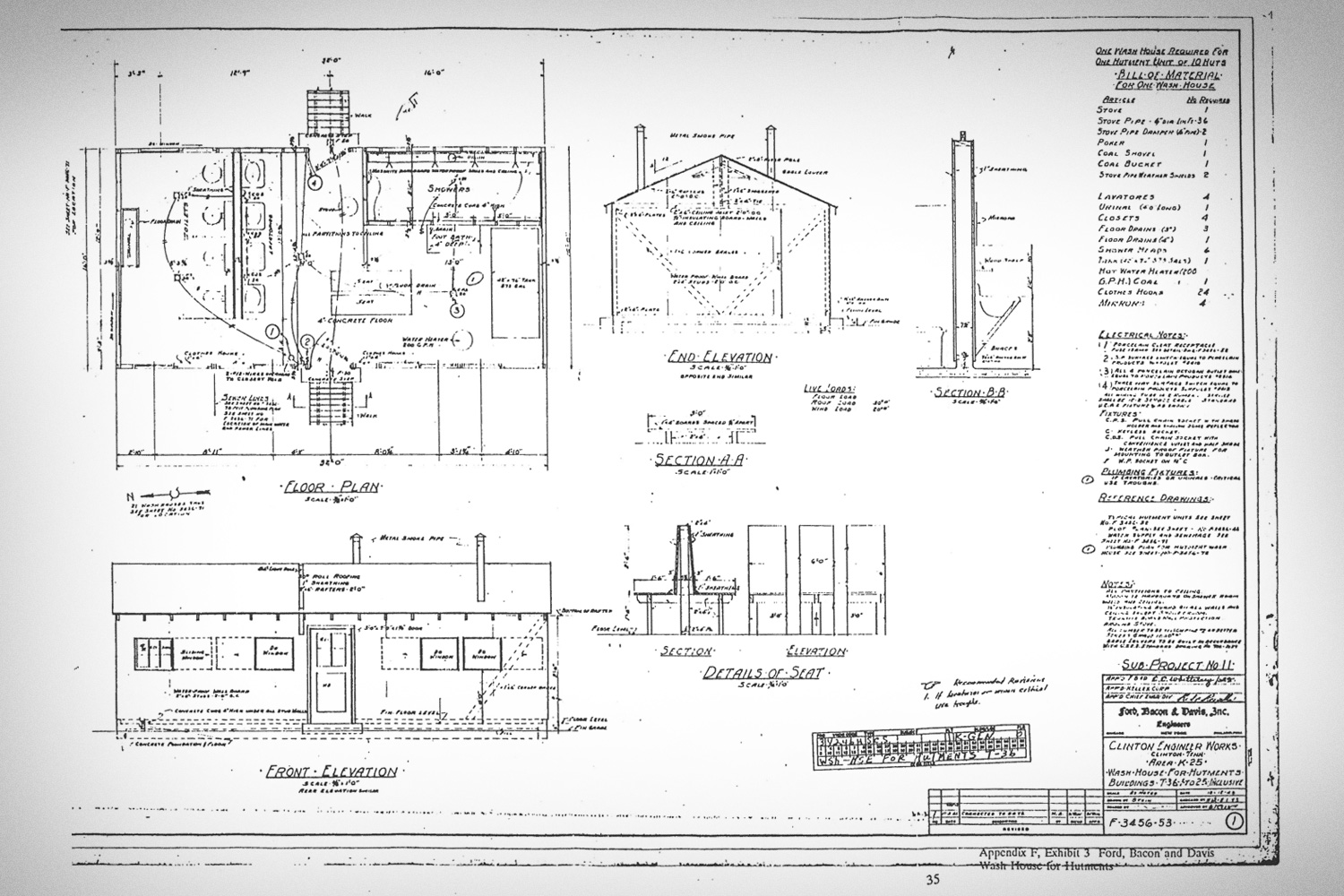

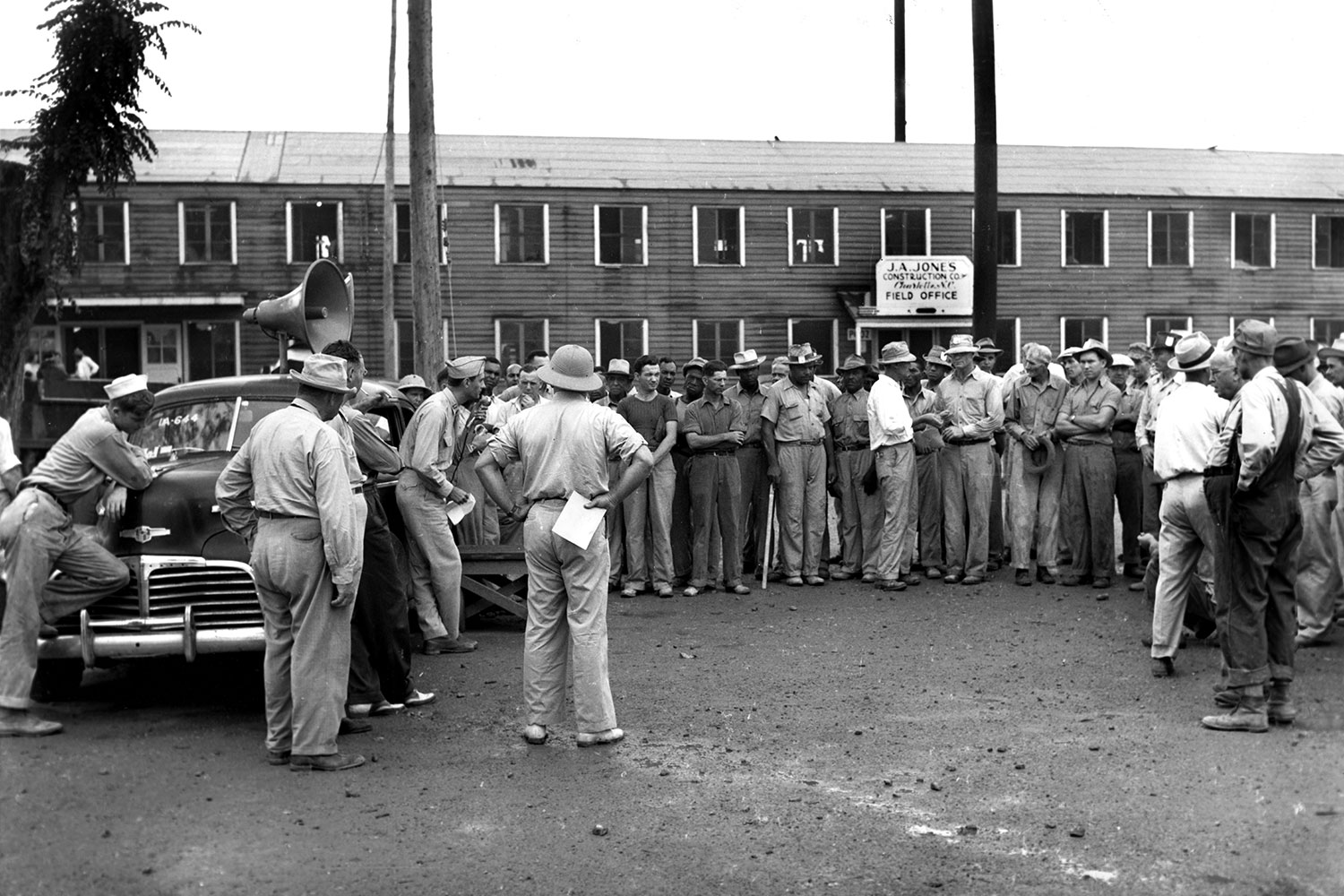

Due to the remoteness of the site and the lack of housing within commutable distance, the Manhattan Project authorized construction of housing camps to accommodate the growing workforce. J.A. Jones and Ford, Bacon, and Davis – primary construction contractors at the site – were tasked with erecting and operating the temporary housing camps. Camps were located as near as possible to work areas. Use of pre-fabricated building materials reduced costs and expedited construction. Trailers, procured from other government agencies, were also used.

JONES CAMP (aka HAPPY VALLEY)

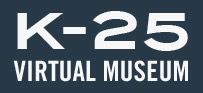

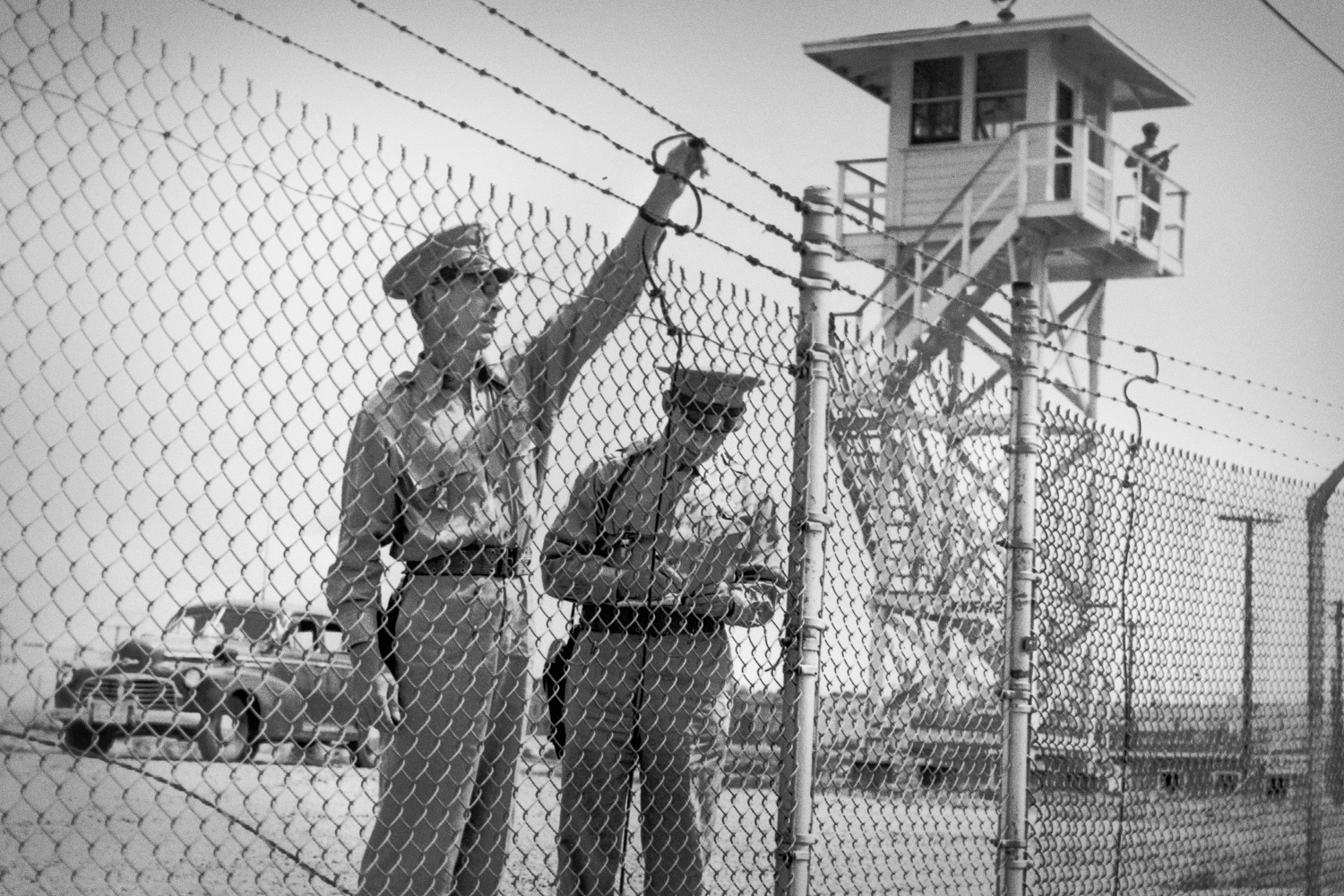

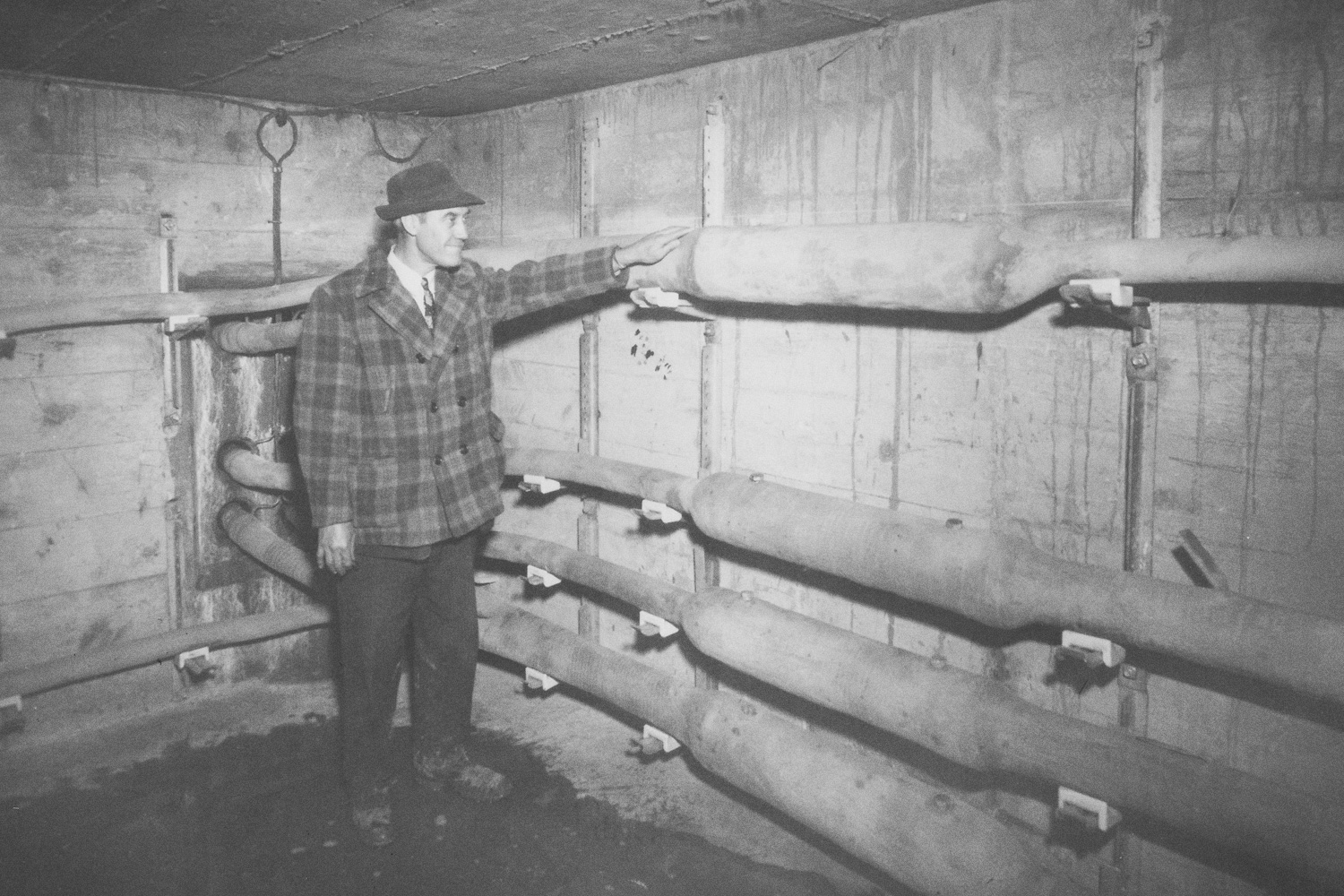

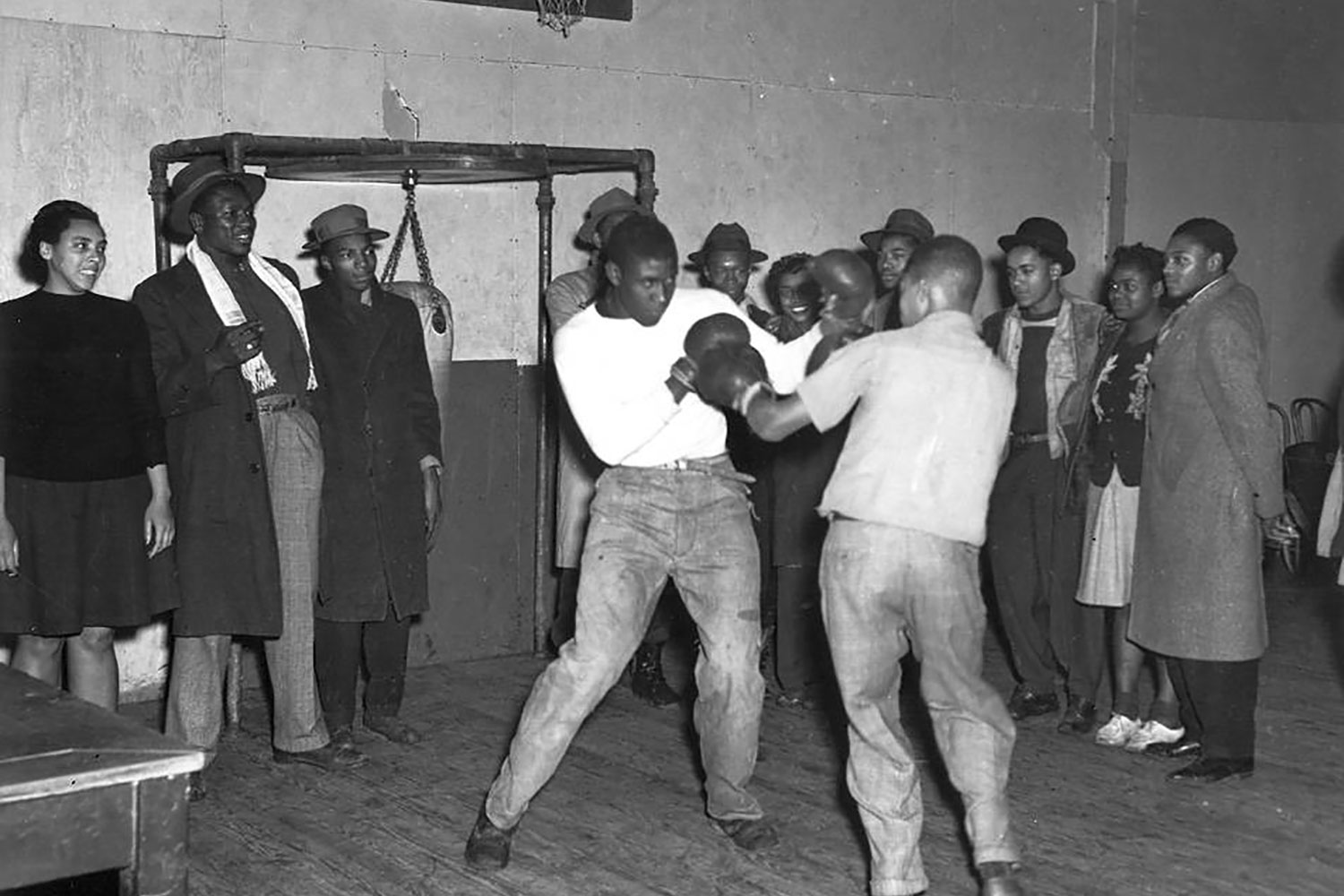

J.A. Jones began constructing the site's first housing facilities in June 1943. The initial compound included 450 hutments and associated cafeteria and washing structures. This area later became a segregated, African-American camp. In this camp, husbands and wives were not permitted to live together and barbed wire fencing enclosed the hutment area for women. Residents dubbed the fenced area “The Pen.” African-American workers were not allowed to bring their children to Oak Ridge until after the war. Like much of the South at the time, segregation was pervasive. As the workforce grew, so did the need for more housing. Ultimately, Jones Camp, later known as Happy Valley, housed 15,000 people in hutments, dormitories, barracks, trailers, and Victory Houses. It included a school, cafeterias, bakery, post office, storehouses, refrigeration and cold storage plant, warehouse, sterilization plant, and camp operations office, as well as a theatre, recreation halls (3), and a bowling alley. A commercial center featured a grocery store, barbershop, shoe shop, and dry goods store. Concessionaires sold more than $2 million worth of merchandise at camp stores.

FORD, BACON AND DAVIS CAMP (aka WHEAT COLONY)

In August 1943, Ford, Bacon, and Davis Engineers began constructing a housing camp for crews working on the Conditioning Building and Fluorine Plant facilities. The camp accommodated about 2,000 people and was called the Wheat Colony. The smaller community contained 244 trailers, 250 hutments, two barracks, one cafeteria, and a lot for worker-owned trailers/campers. One hundred of the hutments were designated for African-American workers. Commercial facilities included a grocery and meat store, barbershop, and beauty parlor. Working parents had access to a day nursery for the care of younger children. In January 1944, a recreation/community hall opened in the Wheat Colony.

In all, the two camps housed more than 17,000 people (another 19,000 construction and operations workers commuted to work each day from various towns, villages, farms, and trailer camps). By 1947, all camp housing facilities had been removed, relocated, or repurposed.

HUTMENTS: A LOOK INSIDE

Thousands of Happy Valley and Wheat Colony residents lived in 16 x 16 foot hutments. The stove-heated units accommodated four to five workers and were located in blocks (usually 10 hutments per block) around central washrooms. Screened windows provided ventilation as temperatures rose. Each unit included a waste basket; coal bucket, poker and shovel; and cuspidor (or spittoon). Each resident was issued a cot, pillow, sheets and blanket, as well as towels and wash cloths.

To learn more about other living quarters and necessities, click below.

Learn More

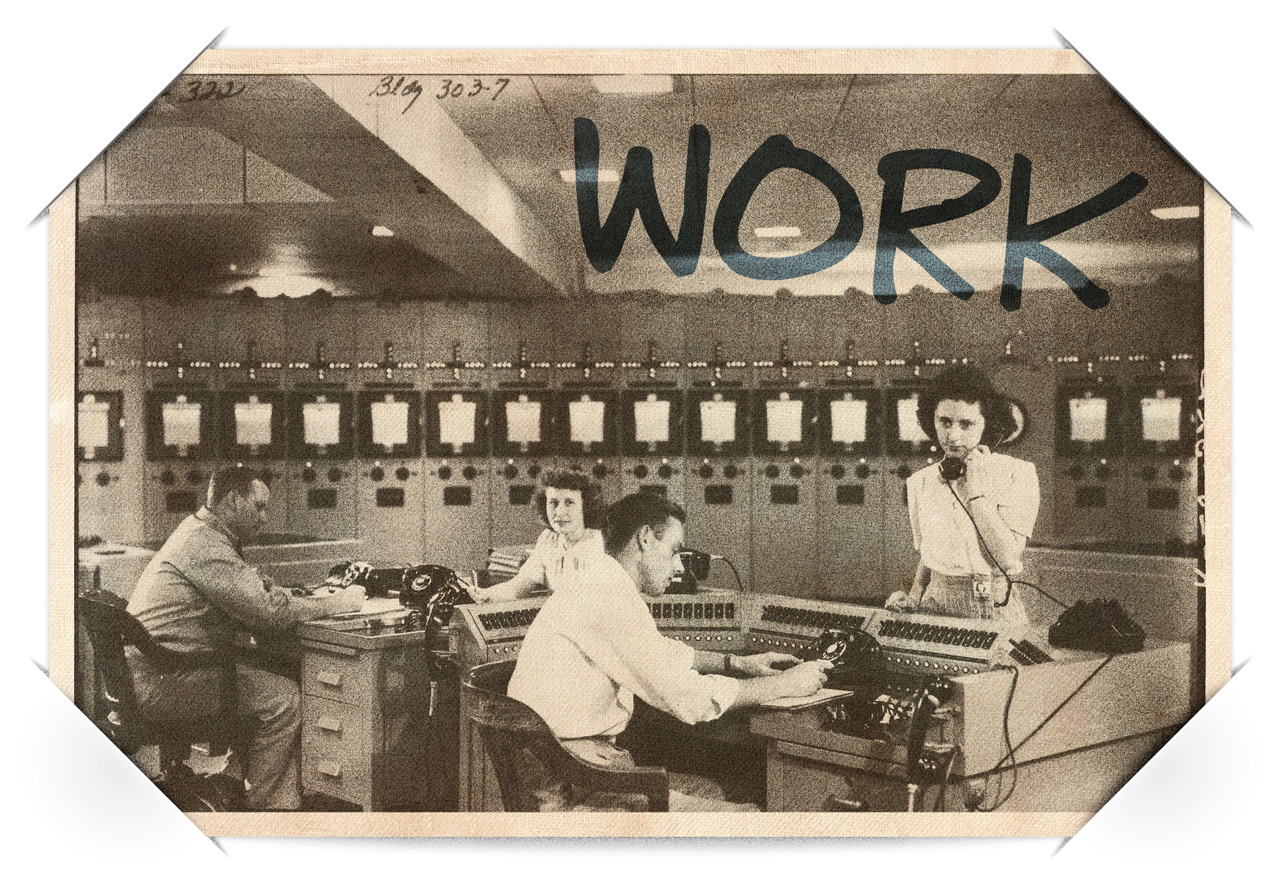

WORK

Thousands converged on the farmland-turned-factory in East Tennessee. Some sought jobs and opportunities not found near home. Others were assigned to a war project, not really knowing their destination. Locals were enlisted through newspaper advertisements or personal visits from recruiters. Their backgrounds would be as diverse as their faces - from scientist to sharecropper; from big city Philadelphia to tiny Auburn, AL; from scholarly to little formal education. No matter what led them to the Project, they would soon unite in one purpose - to help end the war.

The urgency of the production mission resulted in around-the-clock shifts, seven days a week. Cafeterias, grocery stores, and community centers stayed open to accommodate workforce hours. One K-25 worker reflected, "the community was like Las Vegas - it never went to bed."

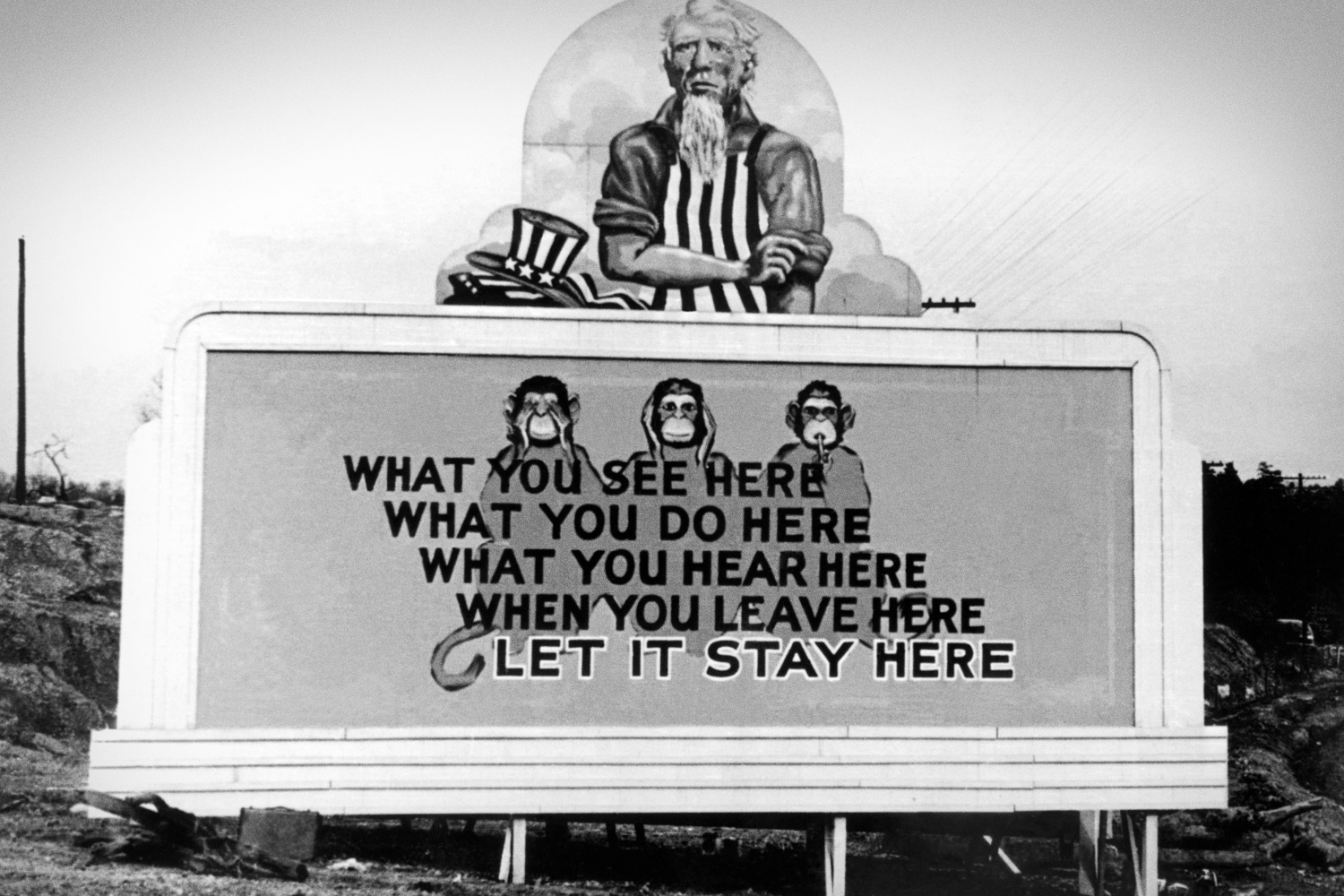

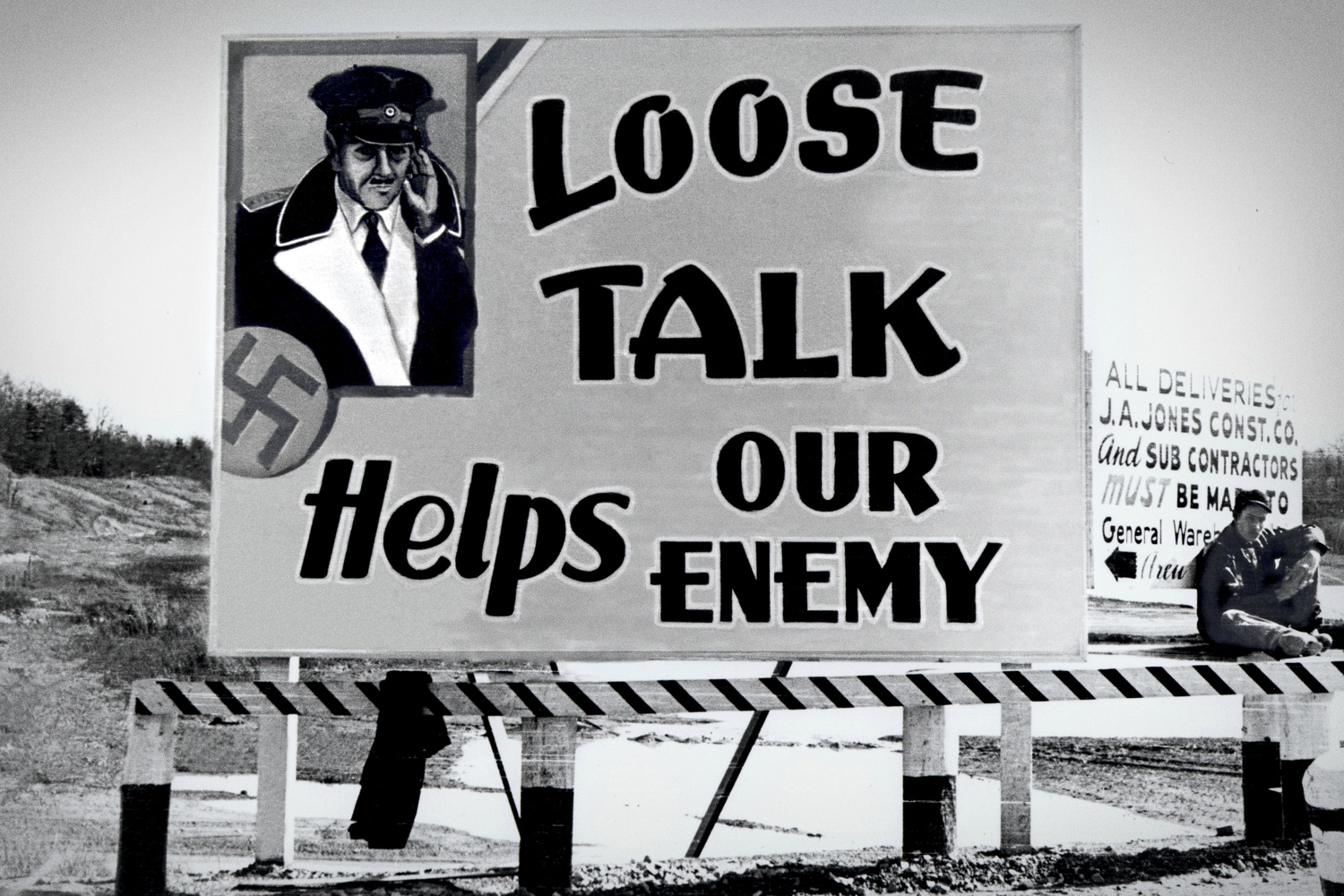

SECRECY

From its beginnings, the Manhattan Project was cloaked in secrecy. Most workers knew little about the ultimate project mission – building the atomic bomb. They were told the project was a secret military effort to support the war. Workers were instructed not to discuss their tasks or job location even with other site workers. From new employee orientation to job training to the daily commute, the workforce was reminded about the covert nature of their jobs.

A NEW LABOR FORCE EMERGES

The labor shortage that was created by the war changed worker demographics. Women of all races and African-American men filled the void left behind by those deployed to the military.

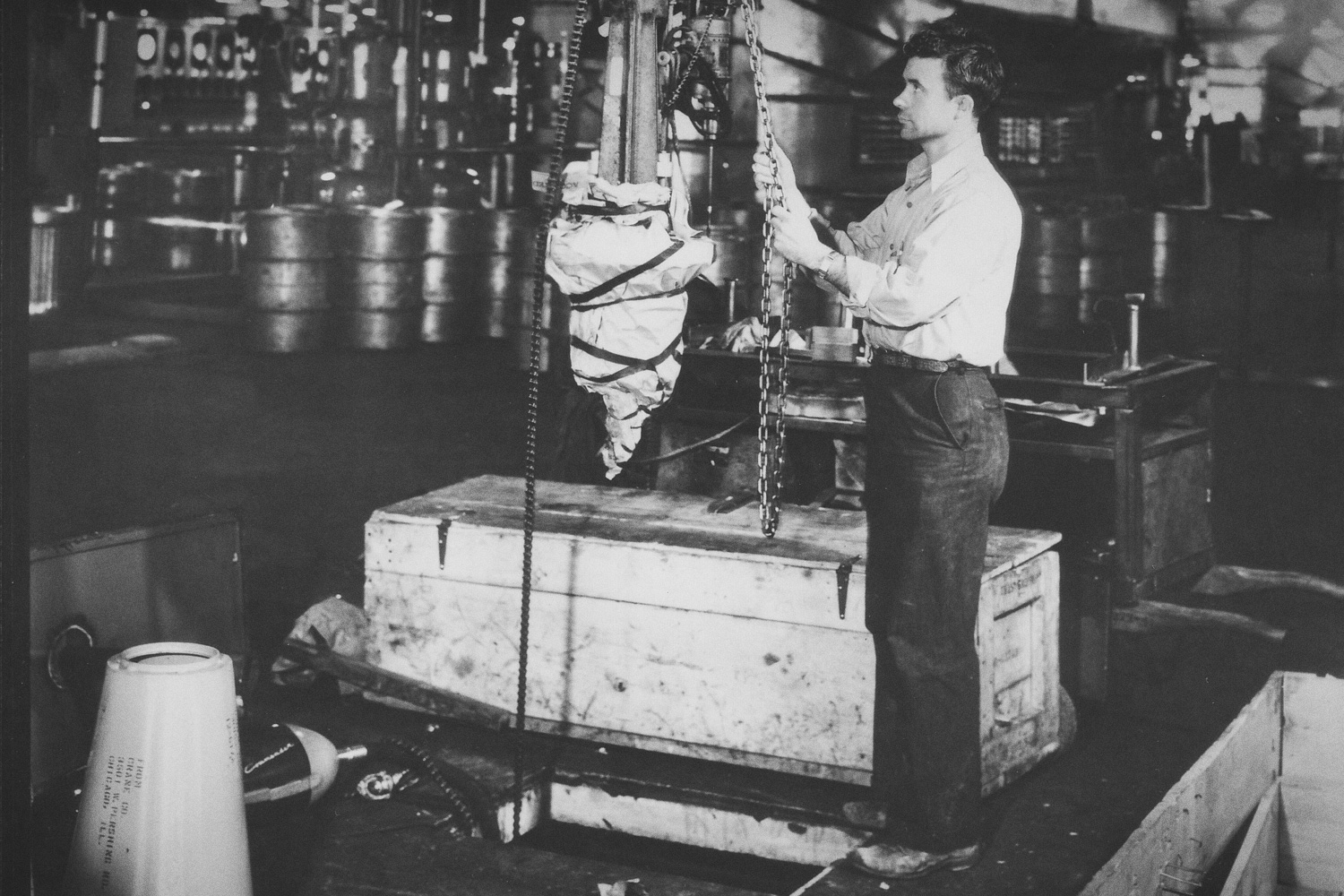

Working under the direction of The Kellex Corporation, women with mathematics degrees and female undergraduate math students supported the K-25 Project as "calculators," first at the New York offices and later at the plant site. As successive units of the K-25 Building came online, increasing production capacity, these women constantly performed complex calculations for various projected multi-plant performance options. Women also served as secretaries, laboratory technicians, medical nurses, chauffeurs, and couriers at the K-25 Plant. Women also provided operations support such as leak testing, brazing, and cleanliness control.

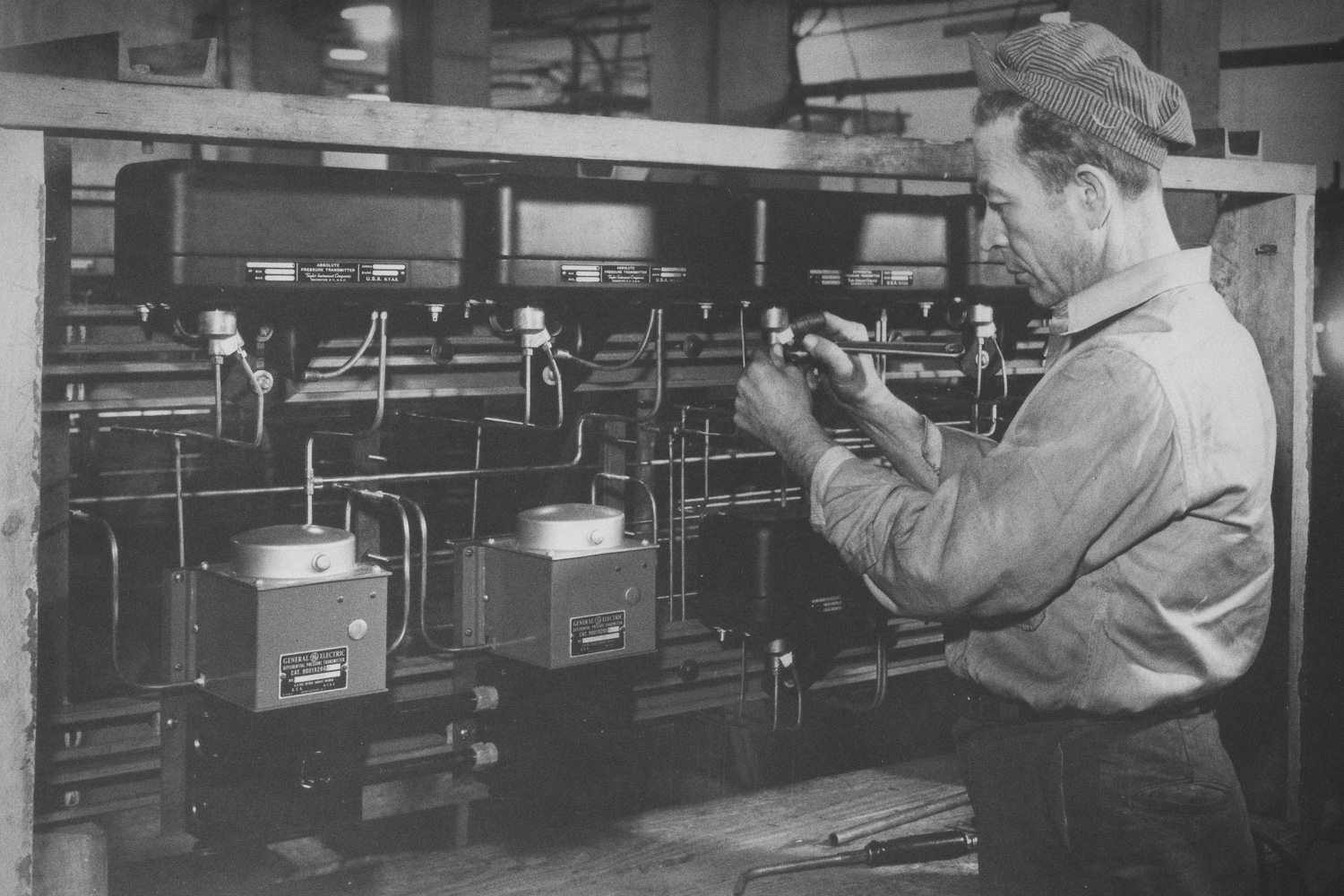

Prefabricating instrument assemblies for installation in gaseous diffusion process system, May 2, 1945.

Prefabricating instrument assemblies for installation in gaseous diffusion process system, May 2, 1945.

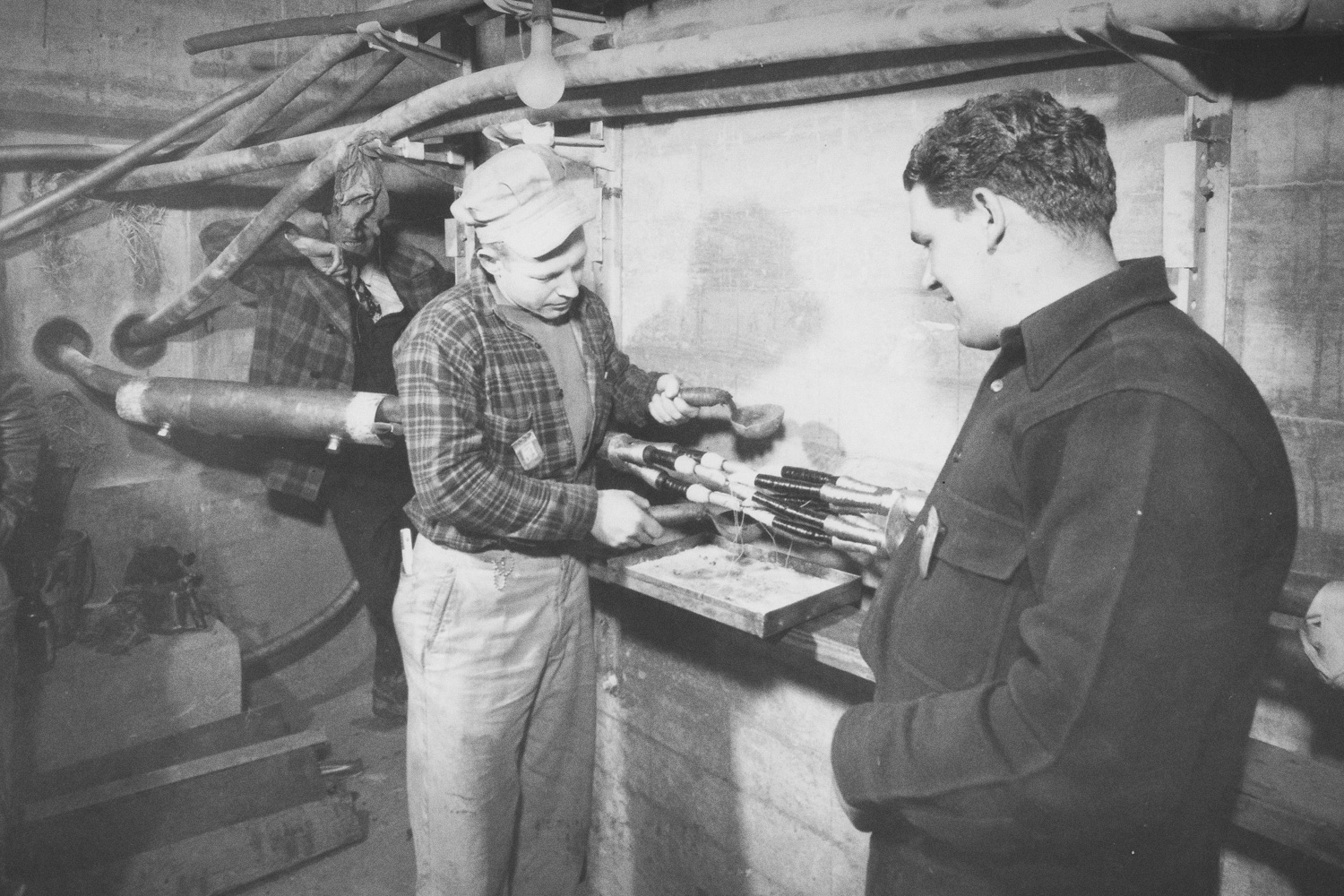

Electrician splicing underground electrical cable that supplied electricity to K-25 Building, March 5, 1945

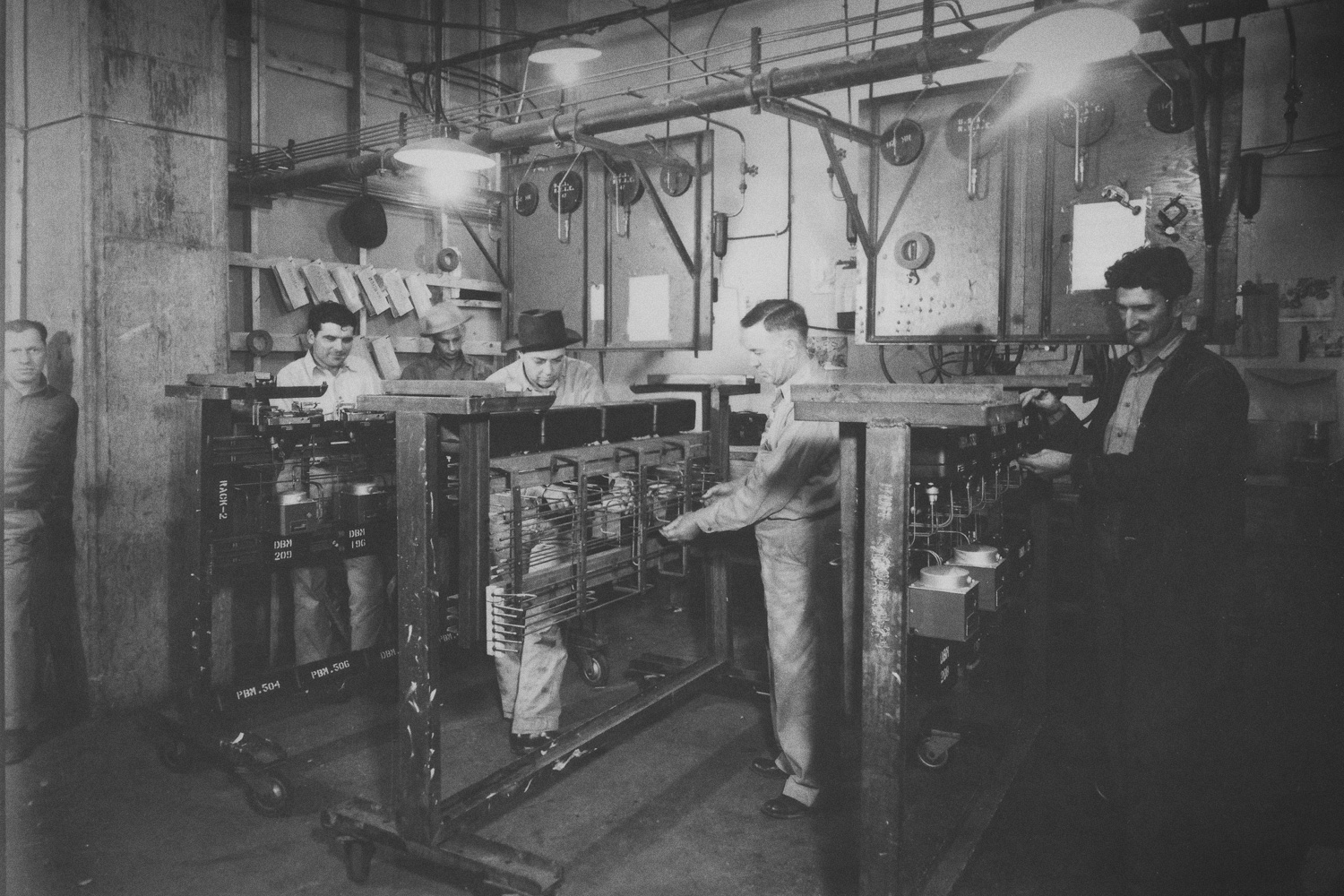

African Americans, though as qualified as white counterparts, were employed primarily as construction workers, laborers, janitors, and domestic workers. Although the K-25 Project conformed to segregation practices of the time and was not immune from racism, many workers were offered an opportunity for advancement. Some were employed by the J.A. Jones Construction Company in crews for setting and maintenance of approximately 24 miles of railroad tracks that were constructed at the plant site; others worked in large crews of highly skilled concrete finishers in the construction of process and auxiliary buildings.

While menial at the beginning of the project, the jobs at K-25 and other wartime facilities became stepping-stones to greater opportunities for minorities in the decades to follow.

Employment peaked in May 1945 when more than 36,000 people worked at the K-25 Site.

"Construction of the K-25, Y-12, and X-10 plants took place almost simultaneously in 1943. Recruiters were sent throughout the region since there was a shortage of workers. Machinists, plumbers, and other skilled workers found well-paying jobs. For the first time, many East Tennessee women had an opportunity to work outside the home."

F. G. Gosling - Office of History and Heritage Resources, U.S. Department of Energy

The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb

GETTING TO WORK

Nearly 50 percent of all K-25 workers lived at the site’s housing camps (see Live); the remainder (~19,000) commuted to work each day from various towns (including Knoxville and the Clinton Engineer Works [CEW] townsite [now Oak Ridge]), villages, farms, and trailer camps. A handful of workers had personal vehicles; however, the majority used the public bus system, established solely for the purpose of transporting workers to job sites throughout the CEW.

Service from the CEW townsite to the K-25 Site began on March 4, 1944. The Bus Authority also arranged commuter service – provided through commercial transportation companies – for those employees living outside the reservation. During March, there were approximately 7,500 passengers. In May 1945, transportation to K-25 Site reached its highest figure, totaling 530,209 passengers. By December 1946, passengers totaled approximately 154,000; 80 buses were required to make between 5,000 to 6,000 round trips. Shuttle services inside the plant perimeter were operated by plant operators and contractors.

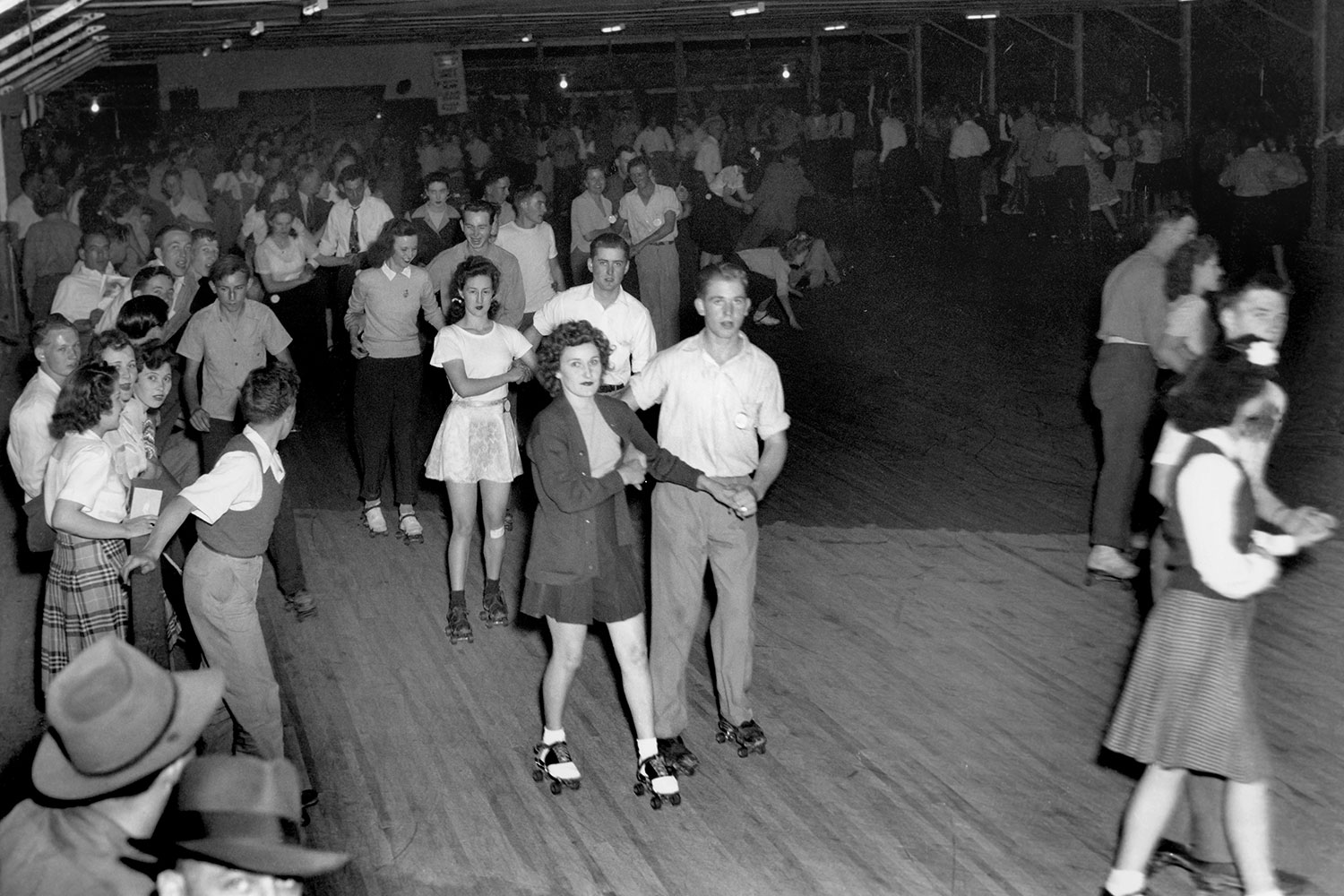

PLAY

Despite the veil of war or perhaps because of it, the yearning for normalcy pervaded. If only for a while, a dance or movie or basketball game gave Happy Valley residents a respite from the darkness and gravity of a world at war.

Happy Valley's movie theatre, built in February 1944, seated 1,200 patrons. Recreation halls and community buildings provided activities for varied tastes from bridge clubs to community sings to horseshoes. For those who preferred bowling or roller skating, Happy Valley had that too.

"At K-25 we had a skating rink, bowling alley, a movie theater, a department store, and a grocery store, and we had a recreation center with a basketball court. And outside we could pitch horseshoes. And that was a laugh, you know, in that time."

Tommy Jones

"Outside of Oak Ridge, there wasn't really much in the way of recreation, so they tried to provide recreation here. Bowling alleys was a big thing. That was one of the things that a lot of the groups at work. They would organize their own teams and then they had a – well, we had a Recreation Department. They did their share on trying to get bowling leagues started and they would sponsor softball in the summertime. But they did whatever they could to make things a little better and a little more sociable, more friendly."

Joe Sawicki